Why the re-investigation team rejects glacial till

Why they say it is a beach

1. Stranded beach lines

The modern Lake Huron shoreline, like many waterbodies, is bounded in places by the beaches we know today. Typically the waves eat into the shoreline, forming a steep bluff, as at left. At various times in the distant past, however, Lake Huron's waters stood higher and beaches developed in places that are now high and dry. The greatest of these ancestral lakes was Algonquin, and "Main Algonquin" beach sediments have been found on hilltops hundreds of feet higher than the Sheguiandah Site.

Over a period of a thousand years or more, the glacial floodwaters gradually subsided. Anytime the water level stabilized for a few tens or hundreds of years, waves cut into soft ground and ate back into hillsides, producing steep banks with beaches at their feet. The muddier sediments were washed out of the glacial till that dominated the emerging landscape, while big boulders tumbled down the slope to lie at the bottom. The intermediate-sized sediments -- sands and pebbles -- were separated from each other by the waves and transported along the shoreline by littoral currents until they reached sheltered places where they could acccumulate. And then the lake waters receded some more. In time, erosion smoothed out the steep scarps, producing bluffs like the one above right, a few miles north of Sheguiandah. The beach deposits would be at the foot of the slope.

Over a period of a thousand years or more, the glacial floodwaters gradually subsided. Anytime the water level stabilized for a few tens or hundreds of years, waves cut into soft ground and ate back into hillsides, producing steep banks with beaches at their feet. The muddier sediments were washed out of the glacial till that dominated the emerging landscape, while big boulders tumbled down the slope to lie at the bottom. The intermediate-sized sediments -- sands and pebbles -- were separated from each other by the waves and transported along the shoreline by littoral currents until they reached sheltered places where they could acccumulate. And then the lake waters receded some more. In time, erosion smoothed out the steep scarps, producing bluffs like the one above right, a few miles north of Sheguiandah. The beach deposits would be at the foot of the slope.

2. Wave-rolled artifacts

Out of the many thousands of specimens Lee found in the 1950s, several dozen had smoothing attributed to being rolled on an ancient beach. On some, such as the specimen at left, the formerly sharp edges have been dulled, the high points are worn down, and the whole surface is smooth to the touch. The tiny inset box (1 cm x 1cm) on one side of this biface is enlarged at right, and placed beside a comparable but unrolled specimen (both about 5000 years old). The surface of the unworn quartzite is faintly grainy, and the ridge where flake scars meet is sharp. On the worn specimen, the surface seems partly polished, and flake scars meet smoothly.

3. Beach sediments are highly sorted

Our stereotyped idea of a beach is pure clean sand. Beach sands lack any muddy sediments to hold them together, so that footprints on a dry beach are just big dimples, and the grains sift cleanly through the fingers like sand through an hourglass. But there are also pure pebble beaches, pure boulder beaches, and pure cobblestone beaches -- like the one at right. Waves separate sediment particles of different size by endlessly washing back and forth, while shoreline currents continuously move them along to different locations, producing the most highly sorted sediments in the world.

Our stereotyped idea of a beach is pure clean sand. Beach sands lack any muddy sediments to hold them together, so that footprints on a dry beach are just big dimples, and the grains sift cleanly through the fingers like sand through an hourglass. But there are also pure pebble beaches, pure boulder beaches, and pure cobblestone beaches -- like the one at right. Waves separate sediment particles of different size by endlessly washing back and forth, while shoreline currents continuously move them along to different locations, producing the most highly sorted sediments in the world. In some places, a beach may contain two well sorted and distinct materials representing different episodes, as on this modern Arctic beach (left), which combines sand and boulders, vividly decorated with seaweed floated in at high tide.

In some places, a beach may contain two well sorted and distinct materials representing different episodes, as on this modern Arctic beach (left), which combines sand and boulders, vividly decorated with seaweed floated in at high tide.

There is a deposit on the Sheguiandah Site that looks so much like this that one would suppose it to have been a beach, too. It lies under the controversial deposits, which are about two feet (0.5 m) thick. The movement of water must have first stripped all the smaller rocks, sand, and pebbles from the boulders, and then, more gently, replaced them with coarse sand -- which itself has been washed nearly clean of finer materials.

There is a deposit on the Sheguiandah Site that looks so much like this that one would suppose it to have been a beach, too. It lies under the controversial deposits, which are about two feet (0.5 m) thick. The movement of water must have first stripped all the smaller rocks, sand, and pebbles from the boulders, and then, more gently, replaced them with coarse sand -- which itself has been washed nearly clean of finer materials.

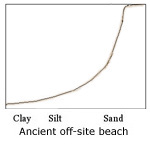

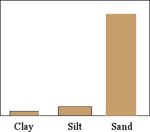

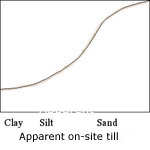

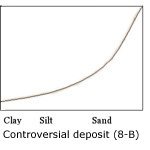

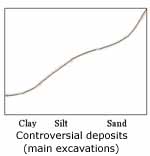

Grain-size analysis is a standardized method of examining sediments. One can imagine that in a bar graph of sediment from a sandy beach (left), almost all the grains would be sand-sized, and almost none having appeared in the much smaller silt and clay categories. Sedimentologists use a cumulative graph, adding the silt to the clay, and then this combination to the sand (bringing the total to 100%), and present it in the form of a line graph (right). The shape of the line tells them what they want to know at a glance.

Grain-size analysis is a standardized method of examining sediments. One can imagine that in a bar graph of sediment from a sandy beach (left), almost all the grains would be sand-sized, and almost none having appeared in the much smaller silt and clay categories. Sedimentologists use a cumulative graph, adding the silt to the clay, and then this combination to the sand (bringing the total to 100%), and present it in the form of a line graph (right). The shape of the line tells them what they want to know at a glance.

The things to notice in such graphs are how straight the line is between opposite corners (indicating less sorting), whether it bends in more than one place, and how much above the lower left corner it starts (higher means more clay).

The things to notice in such graphs are how straight the line is between opposite corners (indicating less sorting), whether it bends in more than one place, and how much above the lower left corner it starts (higher means more clay).

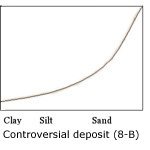

The graphs for a pair of samples from Station 8-B in the controversial deposits (right) show a similar excess of sand, and suggest the sorting action of water. (Station 8-B was a small, rectangular trench dug into a slope on the periphery of the rather level Habitation Area, about 30 feet east of it and three feet lower, down a slope. Some of the deposits, including the controversial ones, appear to be the same in both places, but others, like the subglacial till discussed next, are missing from 8-B.)

4. Glacial till lies below the controversial deposits

Underneath the controversial deposits are sediments that the re-investigation team of 1991 interprets as subglacial till, laid down directly from the base of the glacier. They observed that it is unsorted, having substantial amounts of clay, silt and sand, as shown in the grain-size curve at right. The deposit also includes stones foreign to the site (hence, brought in by glacial ice), and it has a few lenses of clay and silt, which have been said to be indicative of till elsewhere.

Underneath the controversial deposits are sediments that the re-investigation team of 1991 interprets as subglacial till, laid down directly from the base of the glacier. They observed that it is unsorted, having substantial amounts of clay, silt and sand, as shown in the grain-size curve at right. The deposit also includes stones foreign to the site (hence, brought in by glacial ice), and it has a few lenses of clay and silt, which have been said to be indicative of till elsewhere.

The flexure, or double bend in the graph of this till is explained as a result of the probable immaturity of the sediments. That is, the glacier had only started to grind up new material it was picking up from underneath, so that in some ways the till still looks like the original material. This phenomenon affected the grain-size curves for some off-site tills, too (not shown here).

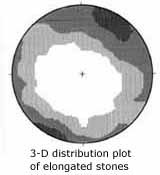

Further evidence for this being glacail till comes from Thomas Lee's fabric studies of 1955, which extended into this layer. He measured the compass bearing and angle of dip on all elongated stones as he dug downward, because the flow lines of glacial ice are usually recorded by the orientation of stones in the glacial till left behind. Computer plotting of his original data for this deposit, shown at left, revealed a tendency for the stones to be aligned with the direction of regional ice movement out of the northeast.

Further evidence for this being glacail till comes from Thomas Lee's fabric studies of 1955, which extended into this layer. He measured the compass bearing and angle of dip on all elongated stones as he dug downward, because the flow lines of glacial ice are usually recorded by the orientation of stones in the glacial till left behind. Computer plotting of his original data for this deposit, shown at left, revealed a tendency for the stones to be aligned with the direction of regional ice movement out of the northeast.

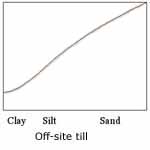

For comparison, the re-investigation team sampled off-site deposits in the surrounding region that they were sure were glacial till. Grain-size analysis revealed more nearly straight-line curves, including the one shown at right. In its high proportion of clay it is similar to the subglacial till deep below the Habitation Area.

For comparison, the re-investigation team sampled off-site deposits in the surrounding region that they were sure were glacial till. Grain-size analysis revealed more nearly straight-line curves, including the one shown at right. In its high proportion of clay it is similar to the subglacial till deep below the Habitation Area.

Problems with the beach hypothesis

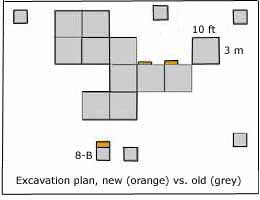

The first problem is that the planned multi-year re-investigation was wrapped up in the first season. Only about two square yards of new ground were opened in the Habitation Area (as shown in orange on the generalized plan of Lee's 10-foot excavation squares, represented by gray at right). Seeing not much more than 1% of what Lee did left the re-investigaton team's interpretation biased by the known variability of the sediments from one exposure to another. They never saw the spearpoint-bearing "Transitional" level, for instance (transitional between the underlying controversial sediments and the overlying humus).

The first problem is that the planned multi-year re-investigation was wrapped up in the first season. Only about two square yards of new ground were opened in the Habitation Area (as shown in orange on the generalized plan of Lee's 10-foot excavation squares, represented by gray at right). Seeing not much more than 1% of what Lee did left the re-investigaton team's interpretation biased by the known variability of the sediments from one exposure to another. They never saw the spearpoint-bearing "Transitional" level, for instance (transitional between the underlying controversial sediments and the overlying humus).

A second problem is that Storck and Julig mistakenly equated the Transitional level Lee reported with an arbitrary depth of 5 to 6 inches, when what really mattered was the association of the spearpoints with that layer, regardless of its depth. Viewed in that light, Storck's own tabulation of Lee's data shows that, in its extremes, the Transitional layer sometimes occurred within an inch of the surface and at others as much as ten inches down. Where his report shows both depth and stratigraphic origin, it can be seen that the spearpoints were found with this layer six times out of seven. Had Storck framed his question more appropriately, his results would have tended to confirm Lee and his view that the soil strata were undisturbed.

Another problem is that the grain-size curve (left) used to determine that the controversial deposits were beach sediments came from peripheral trench 8-B. It is only one of many such graphs from the controversial sediments, and it is not representive of them. Many of the others from the main excavations are very similar to each other and resemble instead what was obtained from off-site till (shown three paragraphs above).

Another problem is that the grain-size curve (left) used to determine that the controversial deposits were beach sediments came from peripheral trench 8-B. It is only one of many such graphs from the controversial sediments, and it is not representive of them. Many of the others from the main excavations are very similar to each other and resemble instead what was obtained from off-site till (shown three paragraphs above). A fourth problem is that one of the features most suggestive of a beach -- the sand-and-boulder layer under the controversial deposits -- raises some rather basic questions. The first thing one wants to know is, 'If this was a Korah beach, why did that ancestral Great Lake leave no other mark on the hill?' The amount of storm energy needed to separate out the boulders should at the same time have cut quite a scarp in the soft sediments at this elevation. It did not. A later, lower lake (Great Lakes Nipissing) has done so quite effectively farther down the hill -- why not the Korah phase of Lake Algonquin?

A fourth problem is that one of the features most suggestive of a beach -- the sand-and-boulder layer under the controversial deposits -- raises some rather basic questions. The first thing one wants to know is, 'If this was a Korah beach, why did that ancestral Great Lake leave no other mark on the hill?' The amount of storm energy needed to separate out the boulders should at the same time have cut quite a scarp in the soft sediments at this elevation. It did not. A later, lower lake (Great Lakes Nipissing) has done so quite effectively farther down the hill -- why not the Korah phase of Lake Algonquin?

Next, 'If the boulder concentration was once a beach, exposed to the open air, where did the overlying controversial sediments come from, and how did they get to where they are now?' Hundreds of cubic yards of material are involved. Processes like mudflow that can mimic till have been ruled out, and movement by water would have separated the fine sediments from the stones.

None of these or other questions, which go to the heart of the beach hypothesis, were addressed in the re-investigation.